Real writers use typewriters—or that’s the way it used to be.

When I was growing up, my mother, who had learned to type in college, owned a portable typewriter. She wasn’t a writer, but she was the typist in the family. My father, who could do just about anything but type, would have her type up the occasional business letter. It always seemed an effort for her to lug out the machine and set it on the kitchen table; for a portable, it was heavy and clunky. It was also old, and I think she used it in college. I remember its musty, oily smell.

It wasn’t until high school, where a typing class was offered, that I began to use a typewriter. My reason for taking the class: I was feeling the urge to become a writer, and real writers, in my young mind, wrote on typewriters. I soon learned that a manual typewriter—which was all that we had in our class—was hard labor. But before long, I was hammering out carefully-formatted business correspondence exercises with the best of them.

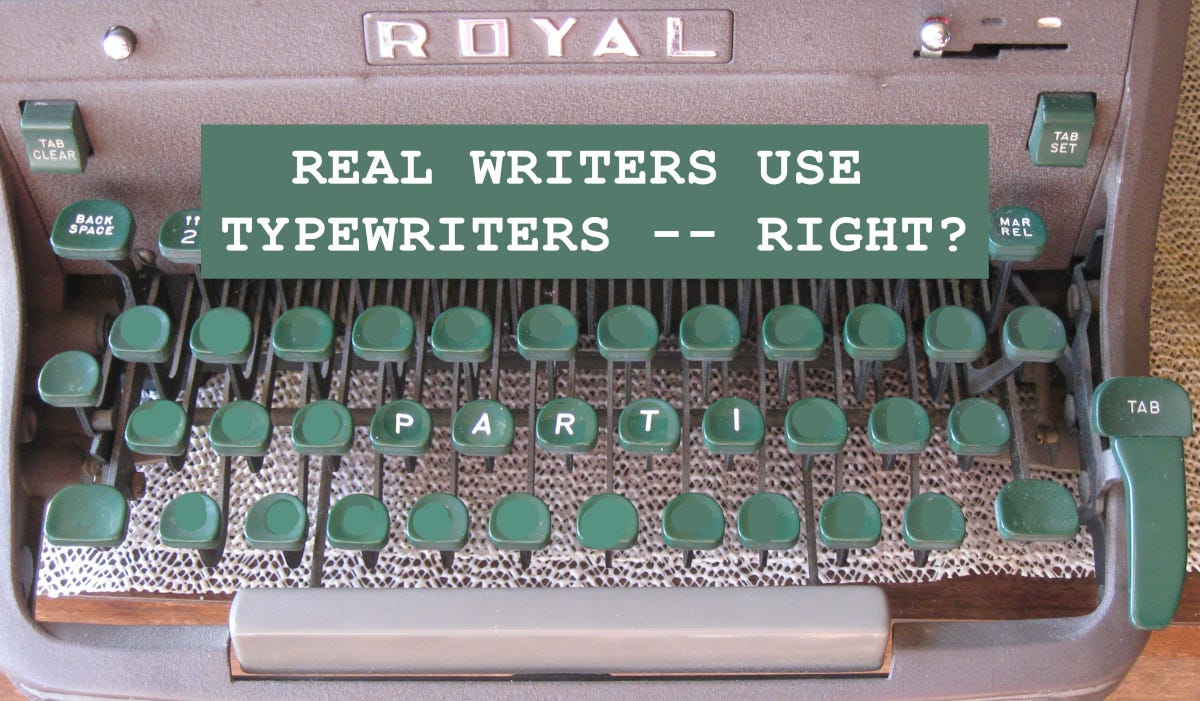

The school did, however, have one typing class that used electric typewriters. For just one day, our class was given access to them. Most likely, the teacher was feeling sorry for us; after all, no modern business used manuals any more. It was a frustrating day, as I had developed a rhythm on the manuals that only jammed the electrics.

Then off to college I went, with a brand-new, portable Adler, perhaps a high school graduation gift. Thankfully, it was a manual. Although pencils (or maybe pens) were still required in the blue book exams, I typed all my papers. This machine also traveled with me as checked luggage on a plane, all the way from Georgia, where I went to college, to Vermont for graduate school.

A moment now, please, to establish a sense of technology at that time: Steve Wozniak was only one year out from having built the first Apple, and I was still five years away from seeing my first Commodore 64. Nobody I knew had a personal computer, much less a printer. Most students had manual typewriters; very few had electrics.

In Vermont, I attended Middlebury College’s Bread School of English. Unusual for a graduate campus, it is set apart from the undergrad campus, 20 minutes away and up in the mountains. The School occupies what had been a summer resort in the late 19th century and still retains much of its pastoral ambiance. Consisting of several rustic cottages gathered around a Victorian Inn, it sits nestled in a vast meadow slung between hills swaddled in maple and birch. For me, it was a true retreat, the quiet of which was only occasionally disturbed by the song of peepers from a distant pond, or the mealtime bell, which the head waiter rang by pulling a rope, or a farm tractor raking hay in the meadow. To make this idyllic setting clearer, think of the poetry of Robert Frost, who taught there in the early days. (His summer home and writing cabin are nearby, if you care to visit.)

But after dinner came the cacophony of typewriters, shattering the serenity. All evening, until quiet hours began at 10, the surrounding hills echoed with the clacks of a hundred or more, the sound spilling out of open windows. In those days, the manufacture of words was a noisy industry.

At Bread Loaf, typewriters occasionally became the object of emotional distress. I vividly remember one student, who lived in my cottage, heaving his typewriter out his second-floor window. He is now a prominent conservative political pundit, and you’ve probably seen him on talk shows or read some of his books. (He’s also the one who flew up a case of Everclear from his home in our nation’s capital for a party, but that’s another story.) Given his success, I imagine he’s healed his relationship with keyboards.

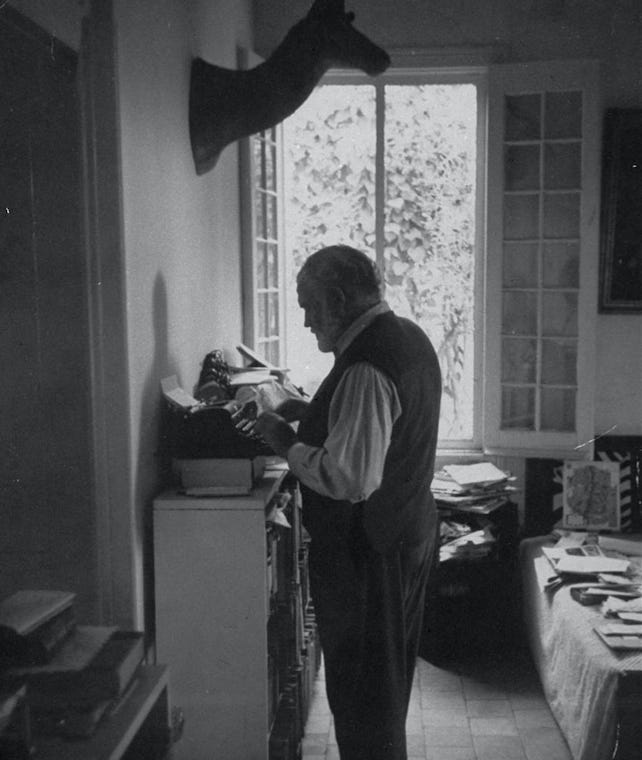

I managed to complete the five-summer program in three summers, which required me to take a heavier load than most. But that final, desperate summer, I became a finely-tuned, high-performance engine, pounding out paper after paper, as I stood upright at a tall dresser upon which I had placed my Adler. I adopted this pose from Hemingway, who also stood to type. I felt I could maintain my energy better, standing.

[Next week, Part 2]